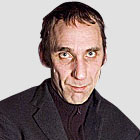

Will Self: The Valley of the Corn Dollies

First published in the Guardian 20 years ago, Will Self's essay argued that, far from being in decline, English culture was changing for the better. This is the form in which it appeared in August 1994

A still from Derek Jarman's The Last of England.

We were standing on the beach at Sizewell in Suffolk – my dad and I. To our right the Kubla Khan dome of the fast-breeder reactor hall gleamed in the wan sunlight. Daddy was expounding. Foolishly I had provided him with an opportunity - I'd admitted that I was writing an article on the state of English culture.

'Mmm . . . English culture. Well . . .' he paused, rocking on his heels, a great dolmen of a man. 'In about 1981 I had to give a lecture at the embassy in Tokyo on the subject of English culture.'

'Oh really.' I was underwhelmed. 'And what did you have to say about it?'

'Funny thing is I can't remember . . . Shall we go and get a pint?'

Not exactly an epiphanic moment but the truth is that the mention of the words 'English culture' prompts more bathetic lines, from more disparate individuals, than anything else I have ever hit on. At times I began to feel that the term 'English culture' might conceivably be an oxymoron, or worse, as flimsy a journalistic pretext as Hunter S Thompson's search for 'the American Dream' in Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas.

Given this, I could imagine the denouement of my quest well enough:

Self floundering across a field of rape in pursuit of a toothless, old smock-wearer.

Self: What is that in your hand old man? Smock-wearer: Thaat? It be a corn dolly .

Self: (capering) At last! At last! I've found English culture! Fol-de-rol! Hi-diddley-hey!

Self and smock-wearer execute a passable Mexican wavelet and then quit the rape field in a severely truncated conga line.

As a fellow-novelist (Irish, of course) put it to me when hearing about my improbable remit: 'The English have such a reliable appetite for hearing what shite they are.' Yes, we may not have a culture we can call our own any more, but never let it be said that we're slow off the mark when putting the boot into it. Indeed, this tendency is now so well advanced that it could reasonably be argued that English culture is entirely constituted by self-loathing.

I'm no stranger to this tendency. I always make it clear when talking about the cultural exhaustion of my country, that I do not mean those other thriving, exciting cultures, tacked on to the edges of the land mass. I dissociate the parlous condition of the 'English novel' from the rude health of the 'English-language novel'. I make damn certain that when I'm in Scotland, Wales, Northern or Southern Ireland, I don't make the absurd solecism of referring to 'British culture'. It would be like a Nazi asking for a cream cheese bagel in Grodzinski's - would it not? Well no, not exactly. The truth of the matter is that while English culture may be moribund when considered in isolation, suspended like some bisected bovine in the formaldehyde of cultural criticism, the reality is that it positively pullulates with invention and polymorphous perversity.

Not all of this is to be desired. Culture cannot be read off from social circumstances in a form of straight equivalence: good society = good culture. The opposite is rather more often the case. Freud, Kraus, Schnitzler, Klimt, Kafka . . . All were working to the full extent of their powers, cradled by the dying limbs of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

It's a bit like this in England. It's all very well for my co-essayists of the last three weeks to trumpet the triumphs - and the weaknesses - of their respective cultures. They may quote this theatre director, synopsise a writer or two and comment on the odd festival, but let's call a spade a spade: their cultures exist like satellites, within the gravitational pull of something far bigger, a kind of cultural dark star, capable of sucking all the available Welsh, Scots and Irish deep into the hinterlands of Portland Place Television Centre, Fleet Street and Soho.

Yes, send us your poor, your huddled masses and we'll dress them in Paul Smith, Agnes B, Vivienne Westwood and Jasper Conran. Then we'll employ them in writing multi-supplement newspapers, filming television retrospectives, Merchant-Ivory films and Carling Black Label commercials.

It would be facile to condemn this as 'cultural imperialism'. No, contemporary English culture is both coloniser and colonised - and all the stronger for it. It is a culture of profound and productive oppositions. And I believe, personally, the best possible country for someone with a satirical bent to live in. I'd go further: England has the world's top satirical culture.

The English have, in the two and a half centuries since Swift (a man who really knew what a reliable appetite we have for hearing what shite we are) ascended a parabola of facetiousness to achieve the very zenith of irony. We have managed this by fostering a culture of conflict and opposition. Is English culture bigoted or liberal? It is both. Is it hermetic and introverted or expansive and cosmopolitan? It is all of these.

One of the recent English cultural events that garnered much attention in the print media was the deathbed interview of Dennis Potter by Melvyn Bragg. Like many other closet Englishmen I felt my capacity for dismissive irony being cauterised and my heart beginning to stir as Potter spoke, saying: '. . . we British in general, English in particular - I find the word British harder and harder to use as time passes - we English tend to deride ourselves far too easily . . . because we've lost so much confidence, because we lost so much of our identity, which had been subsumed in this forced Imperial identity which I obviously hate.' I too find the word 'British' harder and harder to say. It sounds as implausible a description of where I live as 'Airstrip One'. But Potter's televised leavetaking from us was freighted - predictably enough - with irony. For, while setting up a Utopian socialist, essentially working-class culture in opposition to the Heritage Industry, chocolate boxy pomp and circumstance that the current regime still wishes to hide behind, he was nonetheless acting in a way that is possible only in a post-Imperial culture.

His use of television to broadcast the absolute spiritual importance of a 'good death' was not far short of being Ciceronian. Only - I would argue - in England could this have taken place. His dryness, his self-possession, his honesty, his caustic wit in the face of extinction. Damn it all - his sang-froid (as with most quintessential English characteristics, only a French tag will do it justice) made me for a wrenching, choking second or two, proud to be English.

We're big on dignified death at the moment - as suits a culture of rich decline. We were treated to Derek Jarman's expiry in the past year as well. Once again our newspapers, image-hungry and commentful, treated us to photographs of Jarman wasting away with Aids. When he was on the brink of death even the Daily Telegraph carried it as a news item. And this the man reviled for his gayness, his cruising, promiscuous lifestyle and last - but by no means least - his achingly pretentious 'arty-farty' films.

I've been as quick off the mark as the rest of us to dissociate myself from Jarman's creative excesses. As a gay friend of mine once remarked lovingly: 'He just has to put Tilda Swinton in a corner and get her to emote!' There's a tendency among the chattering classes - another of our great coinages - to trash our own before anyone else can. In this sense we're like a collective personification of Anthony Blanche in Brideshead Revisited. We loiter by the statue of Mercury in Christchurch's Peck Quad, desperately frightened lest some gang of vicious hearties come and debag us for our aestheticism.

But the truth of the matter is that Jarman was a great English film-maker. And in The Last Of England he offered us a set of discursive and yet plangent images of our own divided nature: its beauty and its brutality, its sensuality and its darkness. Each frame that Jarman contrived in this film appeared to me to be at one and the same time wholly arbitrary and yet exactly right. The sense of frenzied enervation that it produced in me was unmistakably English in character. After all, as I've often had occasion to remark, London is a great city, that has genuine edge, and which is still in some ineffable way, terribly dull.

So the contradictions pile up. We may bemoan the English for their obsession with class - on some dark days it seems to me that English culture is defined entirely by class preoccupation - yet without this preoccupation it is inconceivable to imagine there being the films of Mike Leigh, Terence Davies or Ken Loach.

While there is a conformist tradition of exploiting class division for 'light comedy' or bogus satire, that runs in an unbroken line from P G Wodehouse, through Waughs (Evelyn and Auberon) to Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie, there is another class-influenced tradition that is surreal, irreverent and genuinely subversive. In the post-war period this begins with Spike Milligan, snags in elements of Alan Bennett and Peter Cook, hooks up the Monty Python team and comes to rest with the alternative comedians of the early Eighties, in particular Alexei Sayle.

That much derided Monty Python team. Oh my God! They ended up in Hollywood, they make corporate videos, they sold out big time! But they were also - let's not forget - good. How good is open to dispute, but they were an Oxbridge gang of bourgeois boys who took on their own class and its preoccupations with a vengeance. They took the piss out of the English ruling class and its mores in a way that hadn't been done on television before, and I don't believe has been substantially improved on since. Let us not forget 'Upper Class Twit of the Year'. And let us not forget either possibly the most incisive film satire on England in the early Eighties, Terry Gilliam's Brazil. Made by a Canadian, I grant you, but infused with all the awfulness of the Thatcher regime, its bizarre elision of antimacassars and atomic weaponry, of aspidistras and the absolutely fabulous.

Thatcher is, of course, the real bogeywoman of this essay. There was never anything more English than Baroness Thatcher nee Margaret Roberts. She proved once again that anyone in this country who had elocution lessons could aspire to a hereditary title. Thatcher made explicit the peculiar cultural bond that has always existed between the English lower middle class and the English upper middle class, the two groups dancing a gavotte around one another, aping each other's attitudes.

It would have been nice to imagine - what with the monarchy so convincingly working itself via the Method into the mind-set of a tampon - that this quavering chord of snobbery was at any rate being stretched in the present if not snapped altogether. But, of course, nothing could be further from the truth. The English obsession with class is in great shape and over the past 15 years has received a booster course of anabolic steroids in the form of Government-inspired promotion of gross economic inequality.

The fact remains that in the past decade and a half in England, the poor have got resolutely poorer while the rich have got resolutely richer. Statistics came out a month ago (rating minimal column inches in newspapers that had more important things to comment upon, such as new trends in advertising), that while the middle classes in England have doubled their wealth in real terms, the least well-off have got progressively poorer.

This leaves the bulk of cultural commentators in an uneasy - not to say tendentious - position of having to nip and nibble at the hand that so conspicuously feeds them. Going back to that Potter interview, I think he voiced a sentiment that many of us feel when he said that there was a real demand for radicalism in England in the Eighties - it happened to come from the right wing, but the demand for change was insistent.

We got the change - but it wasn't exactly what we were looking for. But to reprise what I said above, a great culture is not necessarily derived from an egalitarian or socially responsible political and economic culture. In the Eighties we saw rickets and tuberculosis reappear in our cities along with firearms and crack cocaine, and I would argue that as a direct result England came of age as a particular kind of culture.

A year or so ago I did an interview with Martin Amis for an American college review. It was at the end of our conversation that Amis inadvertently identified the nub of the cultural exhaustion suffered by the English middle class - and what underlies it, adumbrates it, gives it substance.

We were discussing the notion of 'cool'. The Americans definitely had it, opined Amis. All Americans? I countered, or perhaps only African-Americans? They did, after all, coin the term in the first place. Well, Amis didn't know about that, but whatever 'cool' was, it was a quality that the English were incapable of possessing.

I would like to dissent from this view. Not only do I think that English culture is cool - I also think we have been getting cooler. But this 'cool' is a tricky thing. Decidedly double-edged. Cool feeds off poverty and injustice, that's why the Americans have always had so much of it. Cool produces great dance music, great drug culture, the insistent iconisisation of violence and sensuality.

It's fashionable enough to deride America, and to single out its influence on English culture as being wholly negative. A couple of months ago the literary editor of this newspaper, Richard Gott, wrote that: 'There is now no English fiction to speak of, no English theatre, no English art, no English music, no English films, and no English newspapers. What survives is provincial, anecdotal, without reach or significance . . . For years now we have learnt to live with American politics and culture as though they were our own. They are our own for we have no other. We are permanently in a mood to read American writers, see American art, listen to American music . . . etc.' If Gott's rant (another fine English cultural tradition - we even named a political tendency after it in the 16th century), displays anything, it's the bogosity and attitudinising of those on the left just as much as those on the right. The willingness to search for culture in terms of some specious purity. Gott is just as guilty as John Major of longing residually for some English arcadia. His may not be defined by the sound of leather on willow, but it's no more or less asinine.

If Gott wishes to deride English culture in this way because of American influence, then he presumably would also wish to deride the influence of the Afro-Caribbean, South Asian and Central European immigrants to this country, let alone all the myriad other peoples who have made their homes here. (He also presumably has a great deal of sympathy for the way in which New York has been 'invaded' by legions of English journalists, writers and publishers over the past ten years.) Let us not forget that it was England that found a place for Marx to park his carbuncled bum while he wrote Das Kapital, and for Freud to push his couch when Vienna became a tad too intolerant.

And contemporary English culture gifts us the delights of this in the form of: the writings of Ben Okri, Hanif Kureishi, David Dabydeen, Kazuo Ishiguro, Anita Desai, Ruth Prawer-Jhabvala, Caryl Phillips and Salman Rushdie the thoughts of Ernest Gellner, Adam Phillips and Germaine Greer the music of Yehudi Menuhin, Joan Armatrading and UB40 the . . .

If you chuck out the bathwater of 'pernicious' cultural influences, the baby of exciting and productive ones goes along with it. If you see culture as a one-way street you neglect the fact of just how influential English culture has been on the rest of the world - and America in particular. Forget Four Weddings And A Funeral and remember the Stone Roses, the Orb, Primal Scream and the whole Manchester Rave scene, which has washed up in America in just the way that so many other delirious waves of English dance music culture have before.

Yes, you would have to say that, when it comes right down to it, what the English are best at at the moment and have been for some little while - is the synergy of dance, drugs and street fashion. The youth of just about any English provincial city look infinitely cooler - to my mind - than their contemporaries in either Seattle or Turin.

We're also good at something rather numinously termed: 'retail services', by which is meant marketing, advertising and merchandising, as well as franchising. Indeed 'retail services' constitutes the largest part of our invisible earnings. You can go to any city in the world and see the influence of English retail services. How pitiful it is to moan about American consumerism and commercialism when we have so enthusiastically pursued it ourselves for many years.

When I was last in the States, number six on the MTV video chart was Morrissey, as camply English as they go, warbling irresolutely: 'The more you ignore me, the closer I get.' And in truth this is what has been happening with the cool side of English culture, the more the self-appointed elite of cultural critics has ignored it, the closer it has got.

Part of the reason for this is the way that the English middle class excels at cultural appropriation. No sooner has something been generated then it can be twisted into a suitable shape for intelligent 'comment'. Football has been one of the recent victims of this superior yobbism. A lot of rather etiolated, epicene, middle-class, male intellectuals have discovered a new authenticity when they come to identify themselves as football fans.

What are they playing at? After all, it's one thing to enjoy a bit of a kick-around, or standing on the terraces with a plastic beaker of Bovril, but it's quite another to churn out newspaper articles and even books - damn it all, that's culture! And the culture it is is a culture of appropriation. Flagrantly uncool, the English bourgeoisie has gone hunting for new, farouche culture. But it hasn't ventured very far - just down the social ladder a few rungs to raid the working-class larder. And that's what this football thing is about: cultural appropriation. It's really no surprise - because that's what the English pop culture has been about (in part) for many years: ie sons of Dartford PE teachers wailing that they're 'street fighting men'.

There are two nations in England therefore, the cool nation and the undeniably uncool one. It follows that there is a cool culture and an uncool culture. It's the sort of exercise that a great many English journalists take to with great enthusiasm, separating cultural artifacts and creators into these two categories, or others similar. It won't be too long before there are magazines in England consisting entirely of lists of what is deemed to be 'in' or 'out'. Of course the irony here (and please note the frequency with which the word 'irony' is recurring in this essay), is that those who undertake such activities are about as far from the notion of cultural cool as it is possible to be, without relocating to EuroDisney.

Yes, you've guessed it, the arbiters of cool are the least qualified people for the job and further, the vast majority of the people who are responsible for defining the parameters of contemporary English culture are also woefully inadequate for the task. This is not simply a function of the old adage: if you have to ask what rhythm is then you ain't got it. It's more to do with the dread influence of the media and in particular the namesake of Dennis Potter's pancreatic cancer, dear old newly-American Rupert Murdoch.

I'm not going to go into yet another a rant about the deadening influence of television or the parlous state of the English novel, or the lack of quality in the quality newspapers, but certain facts about the relationship between the English cultural scape and the media do seem to me to be indisputable.

In Raymond Chandler's novel The Long Goodbye, the multi-millionaire Harlan Potter remarks, 'a newspaper is an advertising vehicle predicated upon its circulations, nothing more and nothing less.' In the US this was evident as long ago as the Fifties. Here, we have continued to cling to the cherished delusion that the bulk of good newspapers and periodicals are driven by some 'line' or other. But other media - notably television - have now made the same kind of inroads as they have across the Atlantic. English newspapers, magazines and even books now find themselves fighting for a smaller and smaller share of the attention span available. With declining circulations, the only way to bolster profits is by more advertising and cutting editorial costs.

You can now have the delicious experience of opening a quality newspaper and finding many many column inches not only filled with extemporised comment, but also lists of the 'in' and 'out' and most pernicious of all, a vast amount of highly self-reflexive material: journalists writing about journalists, about television programmes, about the way in which certain cultural phenomena have impacted (but not about the phenomena themselves), and about items of such persiflage that you wonder fervently how the subs could bring themselves to key the stuff in. I myself have considered asking all my journalist friends to contribute to a collection of the most facile and meretricious examples of this genre. It would be entitled: The New Glib.

J G Ballard has said that the shocking thing about English television is that it treats serious subjects glibly, the Americans only treat glib subjects glibly, which is a far less serious crime against the culture. What is true about television is also true, mutatis mutandis, about other media as well.

Another contemporary English cultural shibboleth concerns that word 'irony' which I asked you to note earlier. A decade or so ago there was a film scripted by David Hare called The Ploughman's Lunch. This was a state-of-the-nation type film, a timely comment on how the Thatcher era was beginning to shape up. The eponymous, central irony of the film was that the idea of the ploughman's lunch, far from being some immemorial component of English agricultural worker's diet, was in fact the coinage of a Sixties marketing man trying to vitalise pub snacking.

Nowadays such a device would be given the ubiquitous - and invariably incorrect - ascription 'post-modern'. This has come to refer to almost any example of cultural self-reflexivity. It wouldn't surprise me in the least to hear some self-appointed 'cultural critic' refer to the Carling Black Label advertisements as tremendous examples of English post-modernist irony. They're not, of course, they're merely another way that advertising people have hit upon of selling us indifferent lager.

What kind of claim is it anyway to say that while our culture may on the face of it be hopelessly decadent we are at least capable of having a good snigger at ourselves? Such a claim opens the door to a peculiarly unEnglish state of mind: despair. And another concomitant to the specious post-modernist contention, is that the old divisions between 'high' and 'low' culture are somehow being eradicated. The people who advance this view - best summed up by the masthead slogan of the Modern Review: 'Low Culture for High Brows' - are, in fact, our old friends the middle-class football fans under a different guise.

You note that they aren't remotely interested in presenting high culture for low brows, by which I mean that they have no intention of regarding their hold on the print media as an opportunity to provide education or enlightenment for anyone. Rather they seem engaged - and I don't just mean the Modern Review people by this, I think the tendency is far more widespread - in a kind of lower-sixth-form- common-room approach to our culture: it's all much of a muchness really and a bit of a laugh, so let's not take it too seriously. What lies behind this is not the professed aim of elevating popular culture, but the urge to drag high culture down to a level where it can be discussed in the same way that Carling Black Label advertisements are.

I think that popular culture can be good on its own terms and so can high culture. I don't see any particular need to mate them with one another in order to produce some exciting new chimera. It merely seems to me to be the result of the despair that afflicts people when they realise that their culture has simply become too amorphous and too large for them to get any kind of grasp on it at all.

It was said of Coleridge that he was the last man in England to have read everything. Well, he was none too happy with this feat in the early 19th century - imagine what a horror it would be today. It strikes me that while the business of marginal cultures that have had their cultures denigrated and deracinated, is to preserve and renovate them. The business of cultures like England's, that have been and continue to be remarkably influential, is to somehow distress the cultural fabric, so that the people aren't faced with the Coleridgean dilemma. Coming back to newspapers, how many times in the last 10 years have you heard people moan that there is simply too much stuff around for them to read/listen to/watch? Imagine how dreadful this predicament would be if it were really the case that the majority of this material were worth reading/listening to/watching? But of course no nation - not even the English - has a monopoly on the business of cultural self-loathing. Why, even those triumphalists the Americans are no mean practitioners. During a recent book tour of the States if I had been given a dime for every time someone chimed up during the Q & A session at the end of the reading, saying how much better contemporary English writing seemed to be to them than American, I would have become a comparatively wealthy man. When people would say this, there was nothing else to do but point out that most of last year's reading in the English literary press was about just how dismal our literary outpourings were, particularly when compared to those of contemporary America.

But then America is a newcomer to that field of declining cultural self-loathing, and while Americans can attitudinise self-revulsion with the best of us, they still haven't acquired that distinctly English kind of self-abuse, that thoroughly reliable appetite for hearing what shite they are. But I'm confident they'll catch up. They'll catch up because their culture is being changed and compromised in many of the same ways that ours is.

Let me tease this out a bit further for you, and in doing so start to resolve the strange conundrum I presented earlier when I claimed that despite all of this negativity, superfluity, and redundancy, English culture was cool and getting cooler.

All of what I have said above applies to culture when considered as a passively received phenomenon, it does not apply to culture in the making. It most definitely applies to the self-reflexive nullities of much 'cultural criticism' but it certainly does not apply to what these myriad critics are attempting to examine. Let me make it simpler still it applies to the superstructure of our culture, but not to our base. The superstructure of English culture is still overwhelmingly white, middle class and metropolitan. G K Chesterton said that the English love a talented mediocrity and this remains true to this day. The people we are forced to listen to on matters cultural, have by and large seldom actually immersed themselves in the culture they purport to be explaining. They are the cultural PEVists, the Psycho-Empathetic Voyeurs. They no longer need to immerse themselves in culture, they simply need to know that it's going on somewhere. 'Here be culture' reads the map that is attached to almost every publication nowadays in the form of some 'what's on' or events guide.

Although these arbiters would seek to distance themselves from the reactionary postures implicit in so much English culture-mongering from the national curriculum on up, the fact remains that they have joined in a silent compact with those people who believe a culture's strength depends somehow on its purity. They have entered the Valley of the Corn Dollies , and are to be seen there eating ploughman's lunches voraciously. They come under many guises: anti-American, anti-European, anti-Caribbean, anti-Semitic, homophobic, misogynistic, anti-just about anything.

They want to preserve a vision of England that is equally of Lowry and Wodehouse, of dappled afternoons on the croquet lawn at Blandings Castle and be-clogged figures dunking their way across the cobbles of Northern industrial cities. Theirs is a world in which the despair and resentment of Philip Larkin is still the best show in town: It fucks you up your culture/ It doesn't mean to but it does . . .

A pox on all their houses. Last year, along with 19 other unfortunates, I was named as being one of 'the best novelists' (under 40) in contemporary Britain. This ushered forth a storm of cultural self-abuse in the press. Pundit after pundit declaimed on the 'death' of the English novel. Together with my fellow novelists I was somewhat bemused by this. What exactly was it that we were doing if we weren't writing English novels? As you can imagine, there was much discussion late into the night. And while we agreed that a particular kind of English novel, a Trollopian (Joanna or otherwise) crudescence of the national persona, was indubitably extinct (and perhaps never really existed except in the minds of members of the Trollope society), the English-language novel was doing just fine, thank you very much.

Surely the same is true of English culture? While the old idea of a monocultural scape is impossible to sustain, England as the centre of that great roiling, post-colonial ocean of cultural ferment is alive and kicking. So I say: English culture is dead -long live English culture!

No comments:

Post a Comment